On Tuesday, we released a statement postponing our Trial+Error Summit scheduled to commence tomorrow morning. It was the hardest decision we’ve made as a team in the early stages of growth. From a business standpoint, we had many considerations, and I’m happy we chose well. Better yet, that we chose right. In the days since opting to focus on current justice initiatives, I find myself grappling with a new source of anger unique to those of us at the juncture of oppression and creative praxis.

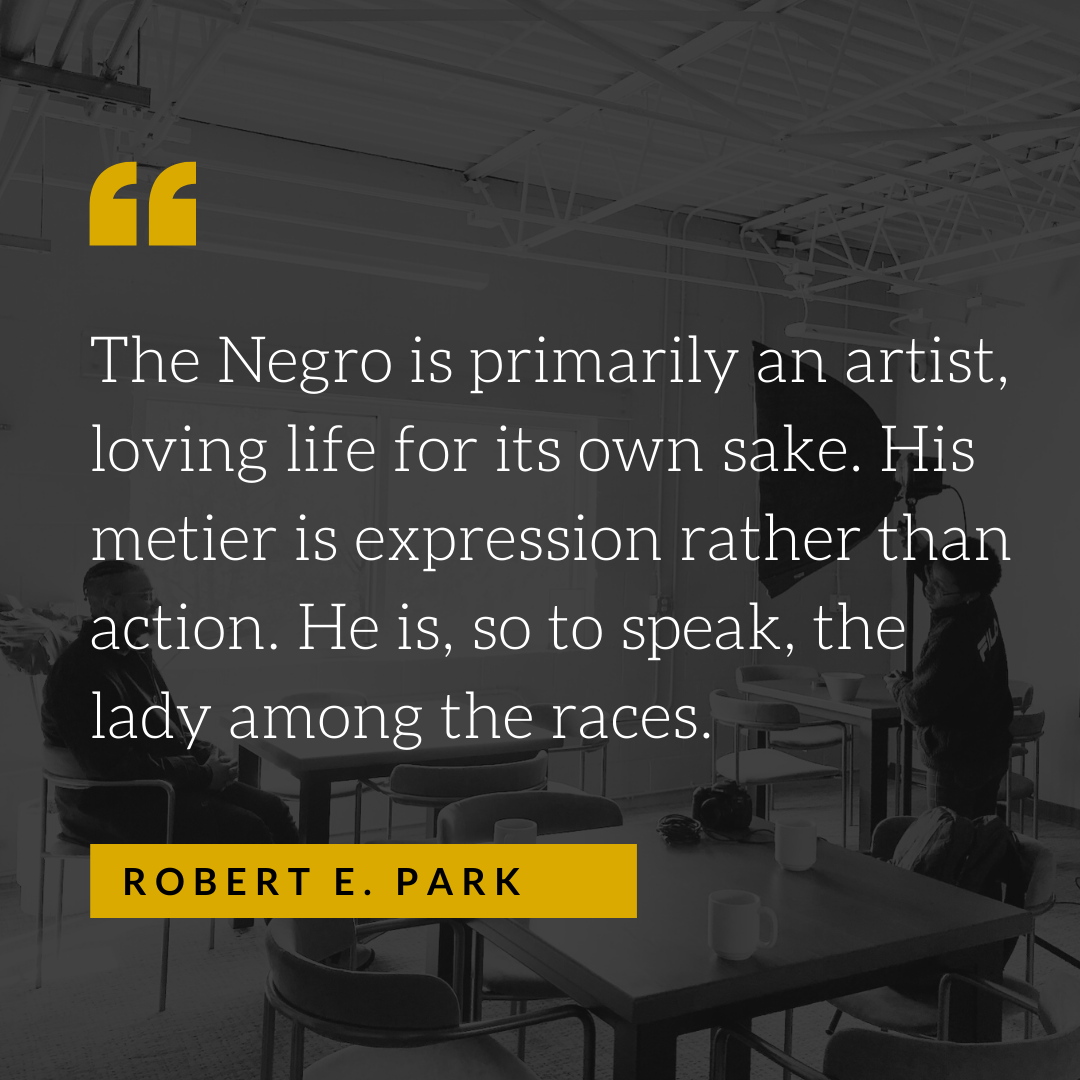

I am weary at how activism is never a choice for the Black artist. *For the purposes of this piece, art/artist is used to encompass all forms of creative output.* While practitioners in dominant cultures are encouraged to create without bounds, Black art is not afforded that same privilege. No matter the artist’s medium – be it visual, textual, sonic or with the body – we are by default working within parameters, and in the overarching industry that is representation. Black art cannot successfully exist outside of activism, which is a site of frustration that restricts the infinite potential of Black creativity. The scholarship and creative processes that inform our work, as a reflex, must center the racism we live through. Thus, even in creative occupations, we are to confront trauma and systemic injustice. No one requires white artists to explore racism in their work, even though the construct is as much a part of their collective identity as the receiving end of racism.

James Baldwin, in 1963, said, “I as a Black writer, must in some way represent you. Now, you didn’t elect me, and I didn’t ask for it, but here we are.”

It is never enough to create for personal fulfillment or livelihood. In the above quote, Baldwin underscores what still reigns true for Black cultural producers of today: Black art necessitates social and political commentary, as a means to legitimize its intrinsic value in the larger world. Why is it that the excluded must recount the factors of their marginalization, in order to penetrate the insiders’ consciousness? This essentially reinforces the otherization of Black life and all it produces. The late African-American Studies and Political Science scholar, Richard Iton, poses a similar question in his exemplary text “In Search of the Black Fantastic.”

Unfortunately, there is no one sufficient answer. Black creatives will continue to weigh the pros and cons of whether or not to include activism as a focal point of their work. It’s telling how cultural products from the collective Black imagination are classified as “Black” art versus just art. As Iton’s book details, art and activism are indivisible for Black creators. That is true for me and the entire Quaint Revolt team. Our solution is to, first, accept that art and advocacy are not mutually exclusive; nor are we able to separate the two. Secondly, activism is not momentary. It requires a series of concerted efforts. Daily practice, if you will.

With those sentiments in mind, we’ve devised a new content strategy to help our community express activism within and outside of creative practice.