Before Roc Nation brunches helped paint the modern portrait of Black excellence in Hip-Hop, a bright young multi-hyphenate from New Orleans gave the music industry an early glimpse at what entrepreneurship and ownership could really look like for Black artists. Since the turn of the 90s, Percy Miller ― or more famously known as Master P ― has proven that there are no limits to what creatives can achieve when approaching their careers with business acumen. Compared to Jay Z, Diddy, and his other contemporaries, Miller is one of rap’s least celebrated moguls, but his name remains in that circle for a reason.

He founded No Limit Records in 1991, the legendary New Orleans record label that predominantly featured southern artists such as Lil Romeo, Mia X, Mystikal, Curren$y, C-Murder, and Silkk the Shocker. By 1995, Miller had inked an unprecedented 80-20 distribution deal, especially for a Southern Hip-Hop label, with Priority records that allowed his label to maintain ownership of the entirety of its masters as well as its recording studio. In 1998 alone, No Limit released 23 full-length studio albums, selling nearly 15 million records and spawning a slew of platinum and gold-certified records.

Miller’s legacy as an entertainment tycoon stretches past his accomplishments within the music industry as well, and in his time removed from the Billboard charts, he has ventured into television and film, professional basketball, professional wrestling, and food. Throughout it all, he has preached the importance of ownership.

As the “Make ‘Em Say Uhh” hitmaker circles back into the public’s consciousness thanks to headlines from the finale of Growing Up Hip-Hop earlier this summer and his recent mentorship of J. Cole ― who reportedly hopes to play in the NBA, much like Miller did during the 1998 and 1999 preseasons for the Charlotte Hornets and Toronto Raptors, respectively ― it’s crucial to recognize the foresight for building and supporting Black businesses.

Miller set the precedent for demanding complete ownership for Black creatives and fully committing to a disruptive ― if not necessarily commercially viable at the time ― brand. The 80-20 deal that he struck with Priority Records in 1995 was unheard of, so for an aspiring rapper from the South to command such a contract was even more impressive. No Limit’s distribution deal was replicated a few years later by Bryan “Birdman” Williams and Cash Money Records, but at its inception, the distribution deals of powerhouse labels like Roc-A-Fella Records, So So Def, and Bad Boy Records paled in comparison, even with more popular and critically acclaimed artists on their rosters.

The label’s acquisition of Snoop Dogg after his publicized split from the infamous Death Row Records further exemplified Miller’s respect for other Black businesses. The horrific lore of Suge Knight has been endlessly reported and speculated upon, but at the time of Snoop’s departure from the label, Miller not only negotiated Snoop out of his previous contract, he guided Snoop along the most respectful path possible during the transition.

“I’m about doing what’s right. I told Snoop whatever you say about Suge Knight, that man did put you on, he put you in the game,” Miller said in a recent interview with The Breakfast Club. “We don’t need to be getting into it with other Black men.”

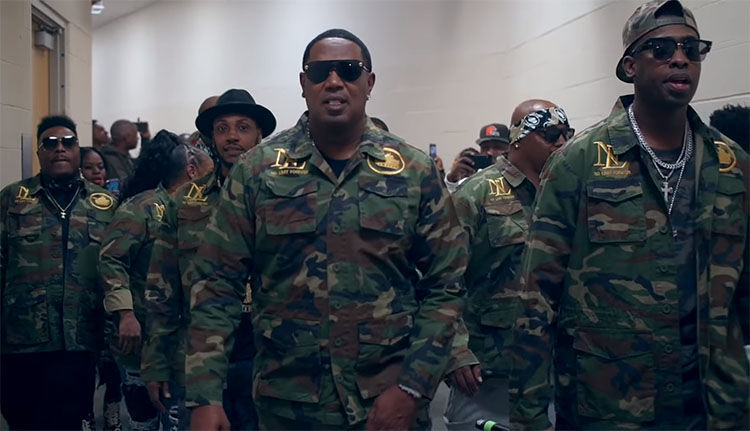

Despite its militant iconography, Miller was never focused on tearing down the work of other Black artists, creatives, and entrepreneurs. Instead, he built a Southern empire through ruthless marketing and a distinct brand identity, from the iconic No Limit Tank to their regularly commissioned Pen & Pixel artwork. In each and every business endeavor ― despite how disparate they might appear ― Miller has maintained an unyielding drive to succeed, leading to his triumphs in music, television, sports, and beyond.

Yet after nearly 30 years since No Limit’s founding, Miller’s most notable feat has been his cutting-edge outlook on properly protecting and monetizing his intellectual property. Master P may not appear in pictures from the yearly Roc Nation Brunch every February, but without his unforgettable run and entrepreneurial ambition during the 1990s, it’s hard to imagine what the contemporary attitudes on ownership and collaboration within Hip-Hop would be like. When Black people fully control their creativity, there is truly no limit.